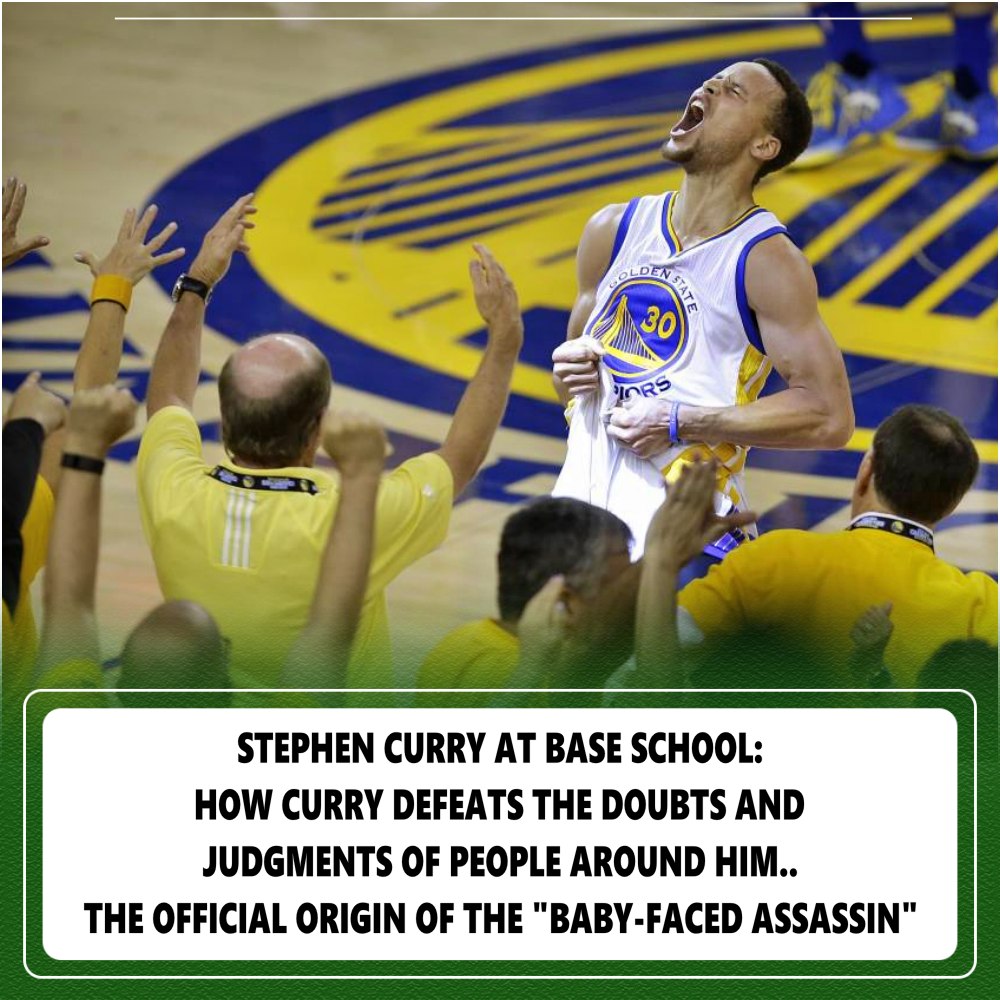

STEPHEN CURRY AT BASE SCHOOL: HOW CURRY DEFEATS THE DOUBTS AND JUDGMENTS OF PEOPLE AROUND HIM..THE OFFICIAL ORIGIN OF THE “BABY-FACED ASSASSIN”

Part of what makes two-time-reigning NBA MVP Stephen Curry so good is the chip he carries on his shoulder. Make that chips. Throughout his career, he’s drawn on lack of respect from his peers, on his draft position, even on the schools that didn’t recruit him in high school—using those experiences to fire his competitiveness, to shift from plain-old best-shooter-on-earth Steph Curry into the ultra-competitor nicknamed the Baby Faced Assassin.

As Marcus Thompson II, the Bay Area News Group columnist who has covered Curry throughout his NBA career, writes in his new book, Golden, “These kinds of moments are peppered throughout Curry’s career. In high school, college, and the pros, there are stories about him shifting gears and destroying his foe. Of him responding to doubt with dominance and slights with something sensational.”

In this excerpt from the book, which comes out April 11, Thompson reveals the origin of the Baby Faced Assassin:

Courtesy of Simon & Schuster

The earliest stories of Stephen Curry’s alter ego date as far back as the early 2000s in Toronto. His mother, Sonya, had moved the whole family, including Steph, his younger brother, Seth, and sister Sydel, up to Canada to spend the year with their father, Dell Curry, as he played his final NBA season with the Toronto Raptors.

Sonya couldn’t find a Montessori school in Toronto so she opted for one of the only Christian schools nearby, Queensway Christian College. A tiny school in the Etobicoke district of Toronto, about fourteen kilometers up the Gardiner Expressway from the Air Canada Centre. Oddly enough, a strip club and the Toronto headquarters for Hell’s Angels were across the street. The school was basically a few classrooms in the back of a church on the Queensway, plus an adjacent portable and decrepit gymnasium that housed all the physical education activities during the thick Toronto winters.

“Soft-spoken,” James Lackey, the Queensway Christian College basketball coach, said of Steph during his time there. “Few words. Real quiet. Friendly. Personal.”

Steph attended as an eighth grader. He played floor hockey, indoor soccer, and volleyball, and then basketball season rolled around.

There were no tryouts at Queensway. The school was so small, everyone who wanted to play was on the team. And usually the same athletes played all the sports.

Lackey started the first practice by rolling out the balls and telling the players to warm up. He really wanted to get a first look at the two NBA player sons, Stephen and Seth, to see what he was working with.

The eldest Curry stood out immediately. As is the case before every NBA game now, Steph’s warm-up was a show. Crossovers, net-splashing jumpers, advanced footwork as he practiced certain shots.

“After about five minutes,” Lackey said, “I went over to him and said, ‘Can you teach me some of those things for my men’s league tonight? I want to use some of those moves on the guys.’ He was doing stuff at age 12 that I’ve never seen before.”

These middle school warm-ups were small potatoes for Curry. He’d been in practice with his father having shootouts with NBA players. He’d give Toronto point guard Mark Jackson all he could handle in shooting competitions. When Sonya allowed him and his brother Seth to attend Raptors games, they’d spend most of the evening facing off on the Raptors practice court—which was across the concourse from a concession stand. Curry would constantly beat his younger brother, swishing jumpers in full-court games of one-on-one. When the fourth quarter began, or when they heard an uproar from the crowd, they’d scamper across the concourse to the tunnels overlooking the court, to see what amazingness Vince Carter had pulled off. After witnessing the replay, they’d run back to the practice court and finish going at it.

They had done the same in Charlotte, when their dad played for the Hornets. Steph and Seth groomed their game against each other in backyard one-on-ones. Steph spent quite a bit of time at NBA practices with his dad, in the Hornets locker rooms, and perfecting his shot on NBA courts. The boys didn’t play AAU ball. The first six years of their schooling was at the Christian Montessori School of Lake Norman, where their mother is founder and principal.

When Curry hit the seventh grade, he transferred to Charlotte Christian. He played for the middle school team. That’s when Shonn Brown, the high school coach, first saw him.

“He could shoot the ball but he was really small,” Brown said. “The way he handled the ball. The way he moved on the court. The way he shot it. You could just tell he had been around basketball.”

So what Lackey saw as amazing was merely a Tuesday for Curry.

As a small Christian college, Queensway’s schedule consisted of playing other similar schools. It wasn’t great basketball by any means, a bunch of short players tossing the ball around, learning the intangibles of teamwork and adversity more than honing their hoop skills. But with Curry on the team, Queensway was suddenly winning by 40 and 50 points each game.

Lackey, for the spirit of competition, started scheduling games against big high schools from the city. Curry torched them, too.

As legend has it, one of the big high schools had enough of Curry—who played shooting guard while his brother ran the point—and decided to get physical with him. Lackey got the sense that the opposing coach told them to bump Curry around.

Lackey tried everything he could to free up Curry, to get some scoring on this bigger, physical team. He put Curry at point guard. He ran him off screens. He used Curry as a decoy. He pulled out fancy plays they hadn’t really practiced.

With about a minute left, Lackey was resigned to their perfect season being over. They were down six points, which at this level of hoops meant you were done. It typically takes four or five trips for a middle school team to score six points, as each trip requires time-consuming plays to get a good shot. He ran out of ideas.

Lackey called a timeout because he wanted to prepare his team for the inevitable loss, use it as a teaching moment about how to handle losing properly. He told them to finish out the game strong, to hold their heads up because they’d played hard against a team they had no business being on the court against.

Lackey, though, did have one move left. He just didn’t know it until Curry spoke up.

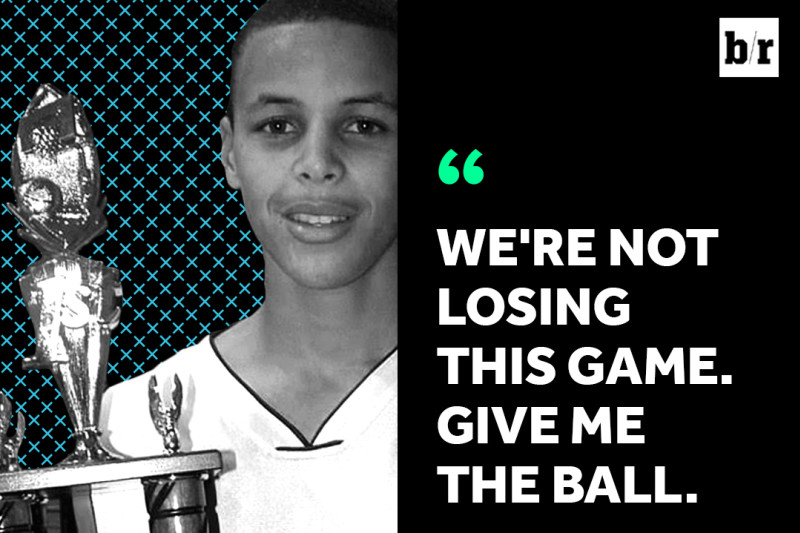

Curry saying anything in the huddle was a surprise. He barely talked. Normally, he would just listen to the play, say, OK, then go run the play. But something had been triggered in Curry.

“That’s when Steph got serious,” Lackey recalled. “He just said, ‘We’re not losing this game. Give me the ball.’ That’s exactly what he said. So I said give the ball to Steph. That’s the play.”

B/R

What happened over the next minute was a stunning takeover. Two quick 3-pointers by Curry rattled the opponent and changed the whole tenor of the game. The Queensway Saints won by 6.

The Baby Faced Assassin was born that day. The alter ego that would turn the kindest, cutest kid around into a vindictive, explosive predator on the court. The Baby Faced Assassin would eventually come out more often, grow stronger and more determined as his basketball career evolved.

Now it is a switch he can flip on and off. Curry is one of the most positive stars the NBA has ever seen. But once he flips that switch, he becomes as mean as it gets on the court. He is merciless in his pursuit of respect. He seeks validation through conquests. He is unconcerned about embarrassing his foe.

The Baby Faced Assassin usually surfaces when opponents are attempting to bully him. But anytime he’s doubted, anytime he gets the sense he’s being sized up, when he bumps against the limitations being placed on him, Curry goes into that zone. When his name is on the line, when he needs to extract respect, his alter ego comes out.

After Dell Curry retired from the NBA in 2002, the family moved back to Charlotte. Curry and his brother Seth, and their cousin Willie Wade, who moved in with the Currys, would hunt for pick-up games in Charlotte. That usually led them to the YMCA in the city.

Inevitably, other players would look at the Curry brothers and think nothing of them. Or they would recognize they were the offspring of an NBA player and look to make an example of them. So many times, they’d leave the court having made believers of their doubters. On several occasions, Curry would enrage his opponent with his shot-making. They couldn’t stop him, so they’d want to fight. But the Currys had an enforcer with them in the older Wade.

“My cousin, he was huge,” Seth said. “He was rough. One of them real country boy enforcers. They didn’t want none with him. We used to run them out the gym. They would get so mad. Maybe it was because of our looks or whatever.”

It was more of the same when Curry got to high school. He landed in another small, intimate setting at Charlotte Christian School. Before the goatee and the muscles, Curry was a giant toddler with his uniform draped off him. He looked more like a kid dressed up as a basketball player for Halloween than an actual player.

Courtesy of Simon & Schuster

But, my, was he good. He dribbled with an impressive command. He could shoot with a range that contradicted his biceps. He passed with a level of instinct most high schoolers don’t have. He was exceptional at changing direction, manipulating angles, and maximizing his short-area quickness though his lack of end-to-end speed trailed most point guards. Curry was an obvious prodigy. Obvious.

“He was as skilled as he is now,” said Oklahoma City guard Anthony Morrow, who starred at Charlotte Latin School and has played against Curry since they were kids. “He was a late bloomer. But you could never leave him open. He never missed open shots. He had everything. He was always a guy you had to make sure you knew where he was.”

The book on Curry was to swarm him. Morrow remembers his team’s plan was to spring traps on Curry. They would fall back on defense, then, when he was bringing the ball up court, they’d suddenly blitz him with a double-team. They screamed and waved their arms wildly, hoping to rattle him into a turnover. They knew they had to do something because once Curry got into the half-court set, it was over. He would break down the defense or get freed by a screen and hit the three.

When Curry finally made it to the state championship game his senior season, Greensboro Day used a strategy the NBA would eventually adopt. Johnny Thomas—a junior small forward who at six-foot-six and boasting the kind of athleticism Curry lacked—drew the assignment of defending Curry. Greensboro Day was more than one hundred miles northeast of Charlotte Christian. But the buzz beat Curry to the North Carolina Independent Schools Athletic Association 3A Championships. And the Bengals had a plan.

Thomas shadowed Curry everywhere, denying him the ball and using his size to frustrate the Charlotte Christian star. Curry had just eight points as Greensboro Day pulled out the championship. Curry didn’t have the strength then. But Thomas got to know the fight trapped inside Curry’s underdeveloped body.

“He was tough,” said Thomas, now a Harlem Globetrotter dubbed Hawk. “He didn’t back down. He came at us all game. We handled him pretty well. He was just too small. I got the best of him that day.”

This has been Curry’s hoop existence, being too small in stature and that being used against him on the court. And his response has always been the same—make sure there is a price to pay. Attack in a way that makes underestimating him become untenable. He likes to make examples out of foes.

One Curry legend comes from the Pro-Am Tournament at Charlotte. At the time it was run by NBA point guard Jeff McInnis, a former Tar Heel who hailed from West Charlotte High.

The Pro-Am was some of the best basketball in Charlotte, which has an underrated hoop scene. Bismack Biyombo, Hassan Whiteside, P.J. Hairston, Ish Smith, Morrow, and the Curry brothers are all NBA players with Charlotte Pro-Am appearances under their belt. And those who grew up in that scene could probably tell you about one night at the Grady Cole Center in downtown Charlotte.

“I remember that,” Curry said. “It was after my freshman year at Davidson.”

Gregory Shamus/Getty Images

Curry playing was an event. He was the well-known son of an NBA player. And he was still slight enough for other players to doubt the hype he received.

They went after Curry that game. It’s not that they were talking trash. But it was obvious to everyone watching that the intensity thrown his way was heightened. The way they defended him. The way they tried to score on him. The way they fouled him. A whole team of players were trying to build their reputation by outplaying Curry.

Curry felt what was happening. After halftime, the Baby Faced Assassin came out. He made an example out of the players who were looking to make a name on him.

“He came back and had like 40 in the second half,” said Morrow, who watched from stands after his team had just played. “And it was 40 just like how it looks now. They were trying to pick him up full-court. I remember his dad went up to him afterwards like ‘You need to play like that from now on. Don’t worry about missing, don’t worry about what nobody says.’ Everybody remembers that. If you know basketball and you come to the Pro-Am, you remember that game.”

If there is a difficulty in having this switch to flip, it is knowing when to flip it. It has taken experience for Curry to master this, and it is still a work in progress. He takes pride in being a point guard. He wants to be known as one who plays the game the right way, unselfish and cerebral. But then there is a part of him that wants to nuke the enemy.

In that way, Curry is a dichotomy on the court, both of his personalities fighting over how to use his considerable talent. It’s as if he gets pulled in two directions.

On one hand, his shooting ability and ball-handling can be used for good. The threat of his 3-pointer spaces the floor and opens up driving lanes. A simple pump fake or mere hesitancy prompts the defense to react. His ball-handling also allows him to penetrate without having to use speed, creating angles for him to pass by his defender and space for him to get his shot. All of those contribute to the purest ideas of basketball. Sharing the rock, making his teammates better, and every other cliche that makes coaches smile.

It’s one of the reasons the Warriors’ motion offense works so well. It is predicated on motion and passing. And the best thing going for it is that Curry buys in, using his gravitational pull to draw the defense toward him and open up the floor for his teammates. It is part of what attracted Kevin Durant, an offense that values diverse skills and feeds off players’ unselfishness.

On the other hand, the Baby Faced Assassin in him wants to use those same skills for evil. They are tools for revenge, to announce his superiority. His range is payback for trying to put bigger players on him. His handles exact punishment for attempts to pressure him.

And the jaw-dropping way in which he wields them both is designed to strike fear. It can be ball-hogging. There is an arrogance to his game, taking shots that for anyone else would be ill-advised, and making them leaves defenses demoralized.

The trick for Curry has been growing the latter while maintaining the former. He is an all-time great because of his ability to be both. But first he had to get comfortable in his skin as the Baby Faced Assassin.