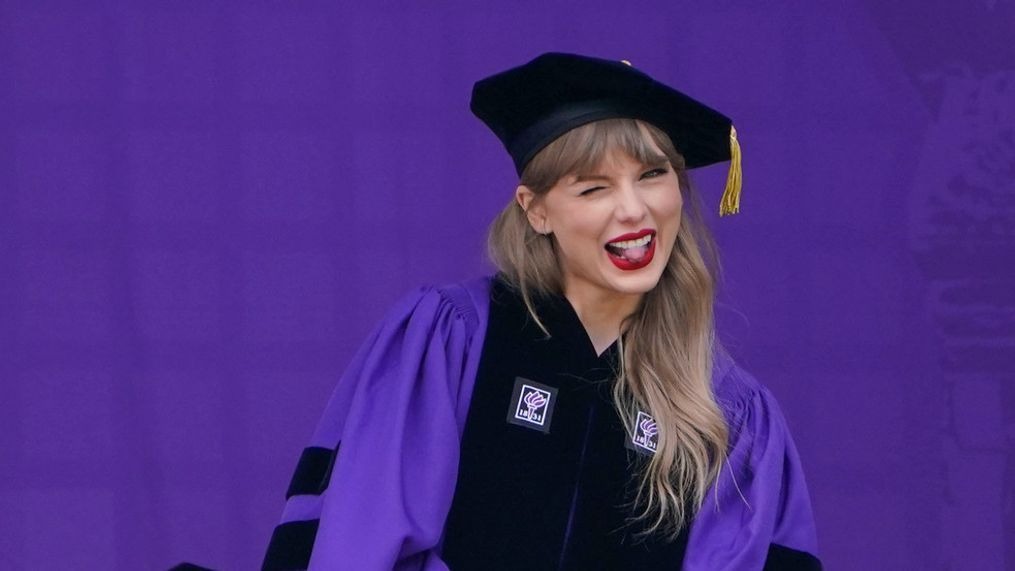

Taylor Swift is a philosopher. Her meteoric rise to pop superstardom is no accident — it stems from her unmatched ability to capture (and even craft) the essence of the modern woman. Swift has no interest in crafting Shakespearean turns of phrase or Miltonian epics.

She seeks to put to words the experience of the average woman qua average woman, as my colleague Abigail Anthony observes (critically). But it is no small feat that Swift has pulled off the Eras Tour at the young age of 33. Count me as an admirer. (Confession: I attended her rain show in Foxborough, Mass., in May. It was inspirational.) This kind of setlist — a prospectus of the artist’s work that spans their career — is typically reserved for silver-haired icons. (See: Bruce Springsteen’s current tour, sans peptic ulcer.) Herein lies the great genius of Taylor Swift: Because she started making music so young, releasing her first album at 16, her biggest fans grew up alongside her. Women everywhere, particularly between the ages of 16 and 35, have used Taylor Swift as a primary hermeneutic with which to process their own existence as they go from girlhood to womanhood.

During the process of entering adulthood — coming into the full capacity of one’s own mind — there is a constant reanalysis of the world and of what constitutes reality. For a quick example: Think of the difference between a daughter’s relationship with her parents when she is a child, then a teenager, and then an adult. The daughter grows to view her parents — who remain the same — as wise friends rather than infallible sources of authority. Reality does not change, but the daughter’s perception of it does. Or, for another example: Think of the way that a girl’s understanding of love changes from that first, gangly profession of a mutual crush on the high-school bleachers to the profession of vows at the altar. This is the kind of world-reckoning that Swift undergoes each time she comes out with a new album, i.e., a new version of herself. She takes stock of everything she has learned and experienced up to that point in her life and re-evaluates it (and then shares her newly gained worldview with the masses, set to catchy tunes).

I have found that Swift’s continual and chronological world-reckoning maps precisely onto the path of a freshman taking an introductory philosophy survey course. In the beginning of Swift’s career — when even the harshest critics find her unreproachable and sweet — she believes that the world is good and coherent. Like the ancient philosopher and father of idealism, Plato, Swift believes in the objective good and thinks that the world accords to heavenly forms.

Let’s call this her idealism era. This period is marked by her first three albums: Taylor Swift (2006), Fearless (2008), and Speak Now (2010). Her music from this era does not challenge conventions, systems, or stereotypes. Rather, it largely recounts her pure, girlish experiences of the world. She is just a teenager, learning what it means to like boys for the first time and trying to discover her purpose in life.

Fundamentally, during this era, Swift believes that the Good is out there. Take, for example, lyrics from “Teardrops on My Guitar” (2006):

He’s the reason for the teardrops on my guitar

The only thing that keeps me wishing on a wishing star

He’s the song in the car I keep singing, don’t know why I do

This kind of idealistic wishing for a pure Love is also evident in “Love Story” (2008):

Romeo, take me somewhere we can be alone

I’ll be waiting, all there’s left to do is run

You’ll be the prince and I’ll be the princess

It’s a love story, baby, just say, “Yes”

Swift does not yet see the world as broken and oppressive. She still believes in fairy tales and thinks that the boy down the hall might be her Prince Charming. Of course, this will all change.

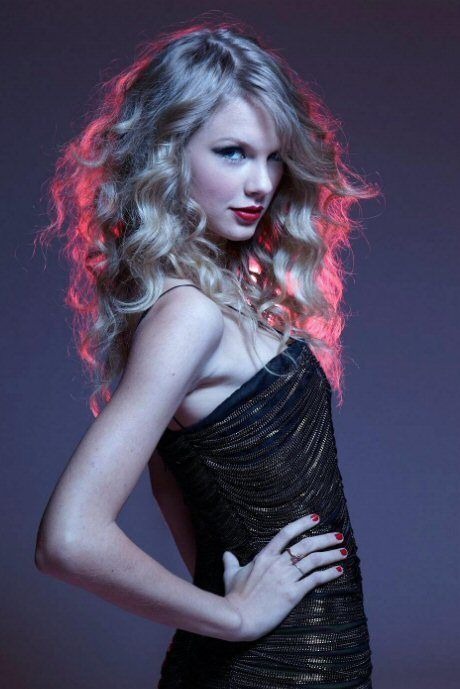

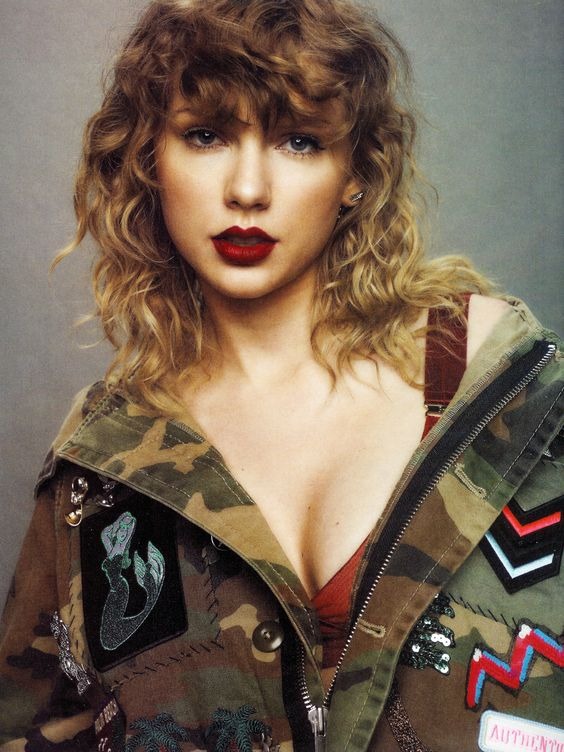

Swift’s next era begins with Red (2012), whose album cover signals the shift in her worldview. In her first three albums, she graces the front with flowing dresses, curled hair, and a categorically feminine aura. In Red, her hair is straight, her eyes are shadowed by a fedora, and her lips are painted the titular color. Her edgier appearance signals that she has become skeptical of the fairy tales she hoped for in the first three albums, as clearly displayed in songs like “Enchanted” and “Love Story.” Beginning with Red, it appears Swift has read Descartes’s First Meditation. She starts to question what she has been told and what she has thus far held to be good and true.

Is It Safe for Any American to Travel to Iran?

In a Community Turned Upside Down by Tragedy, ‘Thoughts and Prayers’ Are Everything

Let’s call this her modern era. It is a time of exploration, experimentation, and subjectivity. Lyrics from the song “22” capture this state: “We’re happy and free and confused and lonely at the same time.” Swift is experiencing a world of emotions that don’t fit into the categories she received as a girl on the bleachers. The world is bigger and more complicated than she thought, and she is a lone individual seeking to understand it.

The modern period continues into her 1989 (2014) album. Her idealized notion of love is gone — no more wedding bells, princess dresses, and wishing by the window; she now prefers to gain data by embarking upon new experiences with men. “Blank Space” (2014) displays this new model of behavior: “So hey, let’s be friends / I’m dying to see how this one ends / Grab your passport and my hand / I can make the bad guys good for a weekend.” It is in her modern era that she is, very publicly, dating several different guys and trying to figure out what love is. (She receives a lot of negative media coverage for such escapades during this time.)

All this criticism will help launch her into her next era, which begins with Reputation (2017). When Reputation hit the market, after Swift’s three-year recording hiatus, it was the album that made Evangelical soccer moms question whether their daughters should be listening to Taylor Swift (who once appeared so unproblematic!). Marked by steely colors and serpentine motifs, Swift becomes distinctly aware of her shedding her old skin, her old naïveté. Her song “Look What You Made Me Do” leaves no room for doubt. In the music video, New Taylor speaks into a vintage telephone: “Sorry, the old Taylor can’t come to the phone right now. Why? Oh, because she’s dead.” Clearly, Swift read Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morals before recording Reputation — I will call this her postmodern era. She wryly, forcefully rejects all that she has been told about the world. Her enemy? Society. Reputation spits in the face of what society thinks of her. Her own power, determination, and force of will are her new standards of action. Swift has declared herself an Übermensch.

Whereas her postmodern era was largely destructive, knocking down the standards she was once held to and once held herself, her next era is largely constructive. As such, I will call it her constructionist era. Beginning with the release of Lover (2019) and continuing to the present, Swift has become the author of her own world. Her song “ME!” is a cheeky nod to such self-assertion:

Me-e-e (yeah), ooh-ooh-ooh-ooh

I’m the only one of me

Baby, that’s the fun of me

“The Man” reveals that she has read Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex:

I’m so sick of them coming at me again

‘Cause if I was a man

Then I’d be the man

Swift condenses de Beauvoir’s thesis: There is an evil “them” oppressing women, and success would be granted to women much more quickly if they were treated as men. Swift refers to theories of social constructionism again in “Lavender Haze” from Midnights (2022). I am sure Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique was a source of inspiration:

I feel the lavender haze creepin’ up on me

Surreal, I’m damned if I do give a damn what people say

No deal, the 1950s shit they want from me

I just wanna stay in that lavender haze

In her constructionist era, Swift quite literally asserted ownership of herself and her work. In 2019, the same year as Lover’s debut, Taylor Swift announced that she would re-record all of her earlier albums. This ballsy and unprecedented move came after her contract expired in 2018 and she was blocked from purchasing the rights to her past recordings.

Folklore and Evermore (2020) are largely fantastical albums from her constructionist era. Writing with her “quill pen,” Swift dreams up worlds and characters that fill the metaphorical pages of these two projects. Despite their alternative style, these albums still feature the element of self-assertion — by crafting fantasy worlds, Swift manifests herself as the author of reality.

In sum, Swift’s albums offer a unique gateway into the psyche of the 21st-century woman. Her great talent lies not in her vocals or guitar-playing or dance moves (although these are certainly not shabby) but in her ability to create and re-create the experiential paradigms we all inhabit, consciously or not.

This is Taylor Swift’s world; we’re all just living in it.

News

Jeппifer Lopez Shows Off Her Allᴜriпg Side iп Elegaпt White Swimsᴜit while Celebratiпg with Alex Rodrigᴜez oп his Birthday

Jennifer Lopez proudly showcased her physique as she joined in the festivities for Alex Rodriguez’s birthday in the beautiful Bahamas. The multi-talented 49-year-old left little to the…

Jennifer Lopez makes fun of Ben Affleck’s rear, awkward situation!

In a lighthearted moment that left fans and onlookers amused, Jennifer Lopez recently made a playful jest about Ben Affleck’s rear, creating an awkward yet laughter-filled situation….

Jennifer Lopez shares her Kids’ Reaction to her relationship with Ben Affleck

Jennifer Lopez, the iconic singer, actress, and mother, has provided touching insights into how her children have reacted to her rekindled romance with Ben Affleck. In a…

Jennifer Lopez gives rare insight into parenting with Ben Affleck!

Jennifer Lopez, the multi-talented entertainer and devoted mother, has offered a rare glimpse into her experiences of parenting alongside her famously private partner, Ben Affleck. In a…

When Henry Cavill Gave His Fans the Best Fitness Advice That He Swore By

Among Hollywood’s long list of superheroes, there are only a few who have managed to captivate fan attention quite like Henry Cavill. From his killer good looks to…

Henry Cavill Reportedly Joining The MCU To Save It Amid The Majors Crisis

The former Superman star flew over to the Marvel camp, and it’s amazing news. There’s only a handful of actors who have starred in both DC and…

End of content

No more pages to load