Troy Reimink: Justin Timberlake’s comeback album says more about aging than he probably intended

“Everything I Thought It Was” by Justin Timberlake.

Reliably for about a decade of my younger adult life, starting in the mid-aughts, at least one stranger per week would say to me: “Hey, do people ever tell you that you look like Justin Timberlake?” And yes, in fact, people did tell me that.

More often than not, this observation seemed like a compliment, although I am agnostic as to its objective truth. Setting aside the gulf of difference in wealth and talent, we are both white men and are the same age, 42, with similarly colored eyes and hair. I think that when I smile or laugh, there could be a discernible similarity that my Record-Eagle mugshot fails to capture.

But I have noticed in the past few years that this no longer happens to me regularly. Now that Timberlake is on the comeback trail — “Everything I Thought It Was,” his first album in six years, was released a couple of weeks ago — I thought perhaps the incidental comparisons would resume. But alas, they have not.

I have identified three possible explanations for this urgent conundrum.

First, time may have eroded our resemblance. Being the same age does not mean we are aging the same way. Timberlake, who presumably has access to expensive skin-maintaining, teeth-whitening and hairline-reinforcement technology, is well-preserved, whereas I am like a deflating Macy’s Parade balloon version of how I looked in my prime (such as it was).

Another possibility is that in order to have strangers compare me to Timberlake, I would need to leave the house. My social habits never fully reconstituted after the pandemic, and the onset of distancing nudged me in the direction I was already heading, away from places where (inebriated) people would be inclined to tell a stranger he looked like a celebrity.

Or, maybe it’s just that nobody likes him anymore. I could not pinpoint when, precisely, everybody seemed to turn on Timberlake, but it vaguely coincides with people no longer telling me I look like him, which I suppose is good news for me.

A negative aura had developed by the time he headlined the 2018 Super Bowl halftime show. The culture had shifted: There was a MeToo reckoning with sexist double-standards in pop culture, and Timberlake was a central figure in two ugly episodes from the 2000s: the Janet Jackson “nipplegate” incident and the tabloid circus surrounding Britney Spears.

It didn’t help that the music had kind of stopped mattering, too. In 2013, he released “The 20/20 Experience,” an overstuffed collage of neo-soul retrofuturism that contained some big hits (“Suit & Tie,” “Mirrors”) but ultimately sagged under its own weight, as did a gratuitous companion album, “The 20/20 Experience — 2 of 2,” that badly overestimated demand.

At the 2018 Super Bowl, he was promoting his next record, “Man of the Woods,” an unfocused mishmash of strained club music and flaccid Americana. The album did not work, and for similar reasons, neither does “Everything I Thought It Was.”

The 18-track, 77-minute effort collects an army of big-name producers and songwriters with a clear mission to resurrect the artful dazzle of Timberlake’s earlier albums “Justified” and “FutureSex/LoveSounds.” The effort does pay off, but probably not in the way Timberlake was imagining.

The lead single, “Selfish,” soulfully harnesses the perspective and contentment that can come with the passage of time. Meanwhile, the wistful “Paradise,” featuring his ex-bandmates from NSYNC, says more about the bittersweetness of aging than he may have intended, capping an album of otherwise labored attempts at the kind of hyper-stylized dance-pop that once sounded effortless.

I don’t know anything about being a successful pop artist, other than it seems like a lot of work to suck in the gut and try to keep pace with the kids year after year. But my experience with getting older is that it goes better the less time one spends trying to capture things — a fleeting resemblance to a celebrity, for instance — that are probably never coming back.

News

Tennis player Ons Jabeur tearfully bids farewell to the tennis world as she announces her first pregnancy with husband Karim Kamoun and confirms her retirement

Ons Jabeur Announces Retirement from Tennis Following Pregnancy News In a heartfelt announcement that sent ripples through the tennis world, Ons Jabeur, the celebrated Tunisian…

Jelena Djokovic raised the alarm: “A lot of people want my marriage to be destroyed and broken with my husband Novak. If you’re one of my genuine fans and you want my marriage to survive and stable, let me see that affectionate YES from you.”

He has become arguably the greatest tennis player of all time and he has a chance to win a 24th major at the ongoing US Open. Many…

Justin Timberlake Passed On His NSYNC Curls to His and Jessica Biel’s Youngest Son

“He’s gonna be me.” -Justin Timberlake, probably. PHOTO: JESSICA BIEL/INSTAGRAM It’s only fitting that on the first day of May, there is Justin Timberlake news to report (cue…

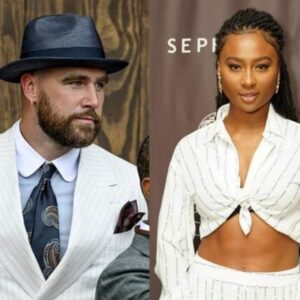

Travis Kelce was spotted by fans wearing an alleged TWIN outfit with ex-girlfriend Kayla Nicole while attending the Kentucky Derby Haf

Travis Kelce was spotted by fans wearing an alleged TWIN outfit with ex-girlfriend Kayla Nicole while attending the Kentucky Derby.. Travis Kelce has officially arrived at the 2024 Kentucky…

Reba McEntire Holds Hands with Her 6-Year-Old Mini-Me Son as Her 1996 ACMs Date Haf

McEntire and her then-little one, Shelby, proudly took on the red carpet together. Reba McEntire has had a mini-me since the ’90s! When the “Fancy” singer attended the Academy…

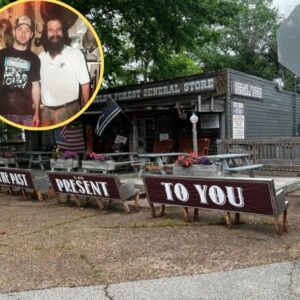

Historic Millington general store Justin Timberlake made famous is for sale

Millington, Tenn. –A nearly century-old general store that megastar and Millington native Justin Timberlake put on the map is on the market. The Shelby Forest General Store, located less than…

End of content

No more pages to load