Look at the premise of No Hard Feelings and you would rightly expect to be scandalised. The film is a broad, affable comedy starring Jennifer Lawrence as a cash-strapped thirtysomething who is hired to “date” a 19-year-old introvert (Andrew Barth Feldman) at the behest of his wealthy helicopter parents. It’s a movie that sells itself on raunch: the button-pushing age-gap romance at its heart leads to plenty of sexually-tinged misadventure, including a much-discussed full-frontal fight scene involving Lawrence. But, as The Independent’s critic noted in our review, No Hard Feelings is ultimately a character piece dressed in sex-farce clothing. Its attitude towards sex all too often resembles that of a sniggering teenager. And it speaks to a problem that is rampant in Hollywood cinema today.

Where once the US film industry was confined by the puritanical restrictions of the Hays Code (the guidelines prohibiting swearing, sex and violence on screen, which lasted from 1934 to 1968), we are now in the thickets of a new censorious era. Sexless action films dominate the box office; long gone are the days when a work of unabashed erotica such as Basic Instinct could take the box office by storm. The bar for sex on screen has been lowered so far that films like No Hard Feelings can win plaudits simply by stumbling over it. The scope for properly explicit adult depictions of sex on screen has narrowed to a sliver.

It’s not just a question of abundance, or quote-unquote “explicitness”, that is the problem. It’s also a question of realism. No Hard Feelings contains a modest amount of sex and nudity, but none of it really rings true to life. I mean, how many naked beach brawls have you been in lately? The one out-and-out “sex scene” sees Feldman’s character ejaculate prematurely between Lawrence’s thighs (off-screen, of course). Sex on screen is nearly always sanitised, romanticised, fetishised, or – as in this instance – heightened for laughs; seldom does it ever ring true. Experts have long warned of the damage that internet pornography is wreaking on the sexual mores of adolescents. Surely a move towards truthful, unembellished sex could only be a good thing?

Often, the argument against sex scenes is framed as a moral issue. It is claimed, or simply implied, that needless sex scenes are exploitative, or otherwise nefarious. Historically, there have been all too many instances of performers getting exploited, mistreated or worse, in the process of filming sex scenes. (Particularly heinous examples, such as Last Tango in Paris, live on in infamy.) But with intimacy coordinators now commonplace in any film or TV set involving sex scenes, the likelihood of these incidents happening has been vastly reduced.

No Hard Feelings wasn’t the only film released this week. Stars at Noon, the latest (primarily) English-language project from revered French filmmaker Claire Denis, slunk quietly onto digital services. Margaret Qualley (Maid) plays a journalist and sex worker stuck in Nicaragua; Joe Alwyn plays an intelligence agent with whom she falls in love. It would be wrong to suggest that the film’s several indulgent sex scenes are the only reason the release has been all but buried in the UK: Stars at Noon is languidly paced and thematically meaty. But it’s also a film by a major European filmmaker that won the Grand Prix at Cannes, and which stars two buzzy young English-language actors. The lack of a theatrical release here is galling – and you have to wonder if the woozy sexual explicitness had something to do with it.

While multiplexes are now often as chaste as chapels, some sultry respite can be found on the smaller screen. Where mainstream cinema has shunned sexuality, television has proved more willing to embrace it. Think of the horny excess of Euphoria, or the dark, sometimes violent sexuality of Game of Thrones. (Though the less said about The Idol, the better.) Perhaps this has something to do with the way the two mediums are consumed: because age ratings are harder to enforce in a home setting, explicit sex does not carry the same financial disincentive it does for a cinema release. Or maybe people are just more comfortable watching a scene of simulated coitus within the privacy of their own front room, as opposed to a dark cinema auditorium, where you could be sat amongst God knows who – vicars, perverts or cackling teens.

To see No Hard Feelings become a hit would be heartening: the film industry needs more comedies like it. But let’s not pretend it tries to say anything real about sex. The problem is – in Hollywood at least – neither does anyone else.

News

Leaked Media Plan Says Travis Kelce & Taylor Swift Will Announce Their Breakup This Month – But His PR Company Says It’s Fake

Are we in the final month of Tayvis? UPI/Alamy Live News Ever since going public with their relationship last year, Taylor Swift and star Kansas City Chiefs tight end Travis…

Ben Affleck is pensive while leaving his office after ‘moving his things out’ of $60M mansion he shared with Jennifer Lopez as she smiles in new video

Ben Affleck and his ‘estranged wife’ Jennifer Lopez seem to be on two different planets these days The 51-year-old Oscar-winning star looked far from thrilled on Thursday…

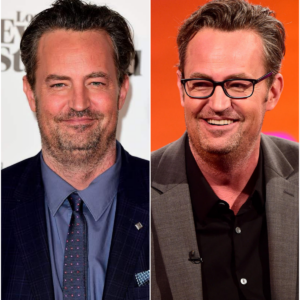

Doctor and ‘ketamine queen’ to face trial next year over death of Matthew Perry

A doctor and a woman dubbed “the ketamine queen” will face a joint trial in March 2025 following the death of Friends star Matthew Perry, a judge…

EXCLUSIVERHOC’s Tamra Judge, 57, reveals pain from ‘brutal’ brow lift and CO2 laser treatment – as she swears off having more plastic surgery

Real Housewives of Orange County star Tamra Judge has vowed to stop going under the knife after a ‘brutal’ brow lift, CO2 laser facial and chemical peel left her in…

Jennifer Lopez and Ben Affleck’s split could ‘get ugly’ due to lack of prenup ahead of their Las Vegas elopement

Jennifer Lopez and Ben Affleck are doing their best to amicably divide their assets, but the process hasn’t been easy. As the stars negotiate the end of their two-year marriage with…

Gigi Hadid, 29, and Bradley Cooper, 49, pack on the PDA as she shows off her stunning bikini body while on family getaway in Italy

Gigi Hadid bared her bombshell bikini body as she and her shirtless boyfriend Bradley Cooper frolicked on a yacht off the Italian coastline during their summer holiday. The 29-year-old supermodel,…

End of content

No more pages to load