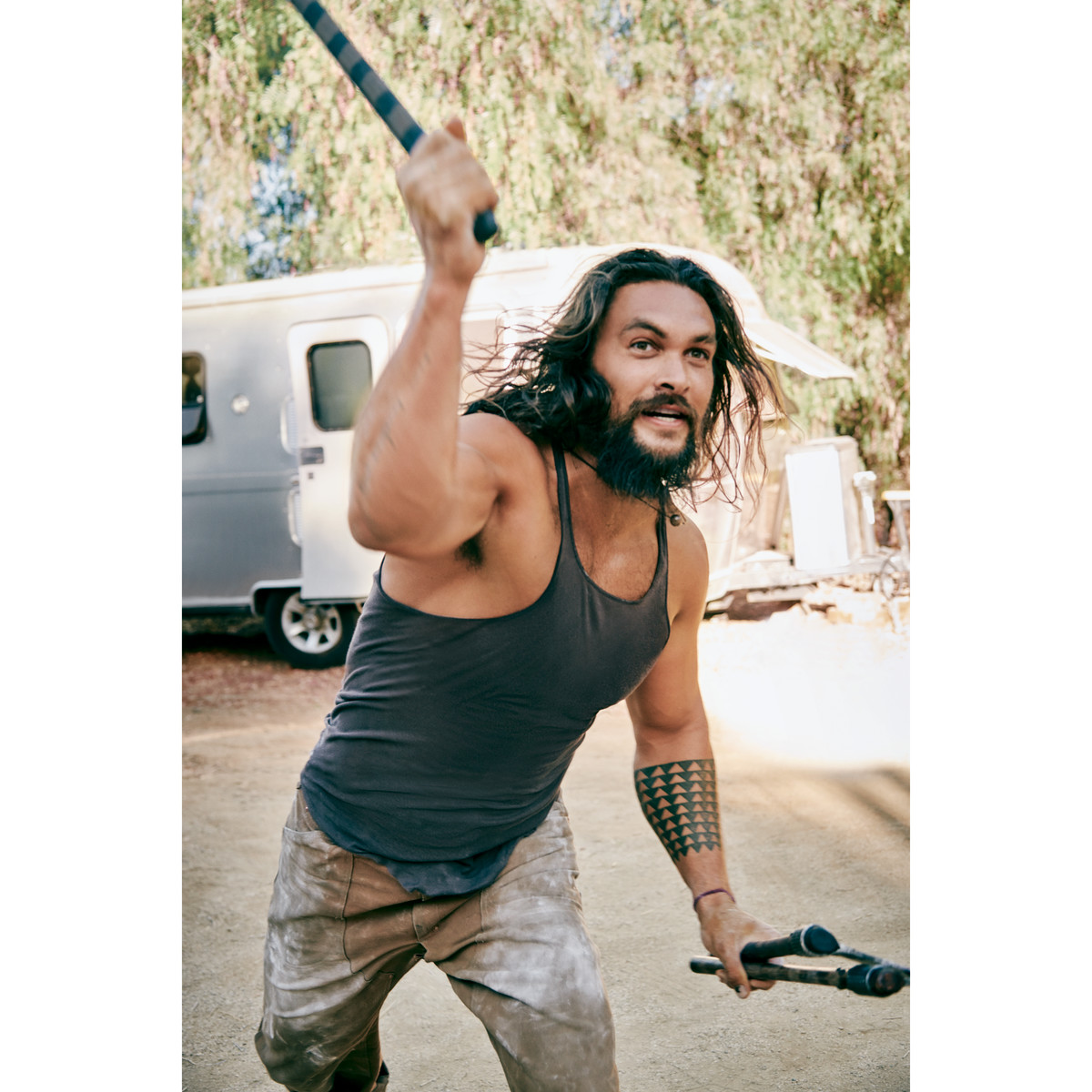

He lives like an action star—climbing, surfing, riding a Harley, and hucking tomahawks. Now, with ‘Aquaman’, Jason Momoa finally gets top billing as a big-screen superhero.

SHOULD I TRIGGER PREMATURE LABOR hurling this ax, at least I know that Jason Momoa’s catcher’s-mitt hands are here to help deliver the baby.

This is what I’m thinking as I stand next to the hulking 6’4” actor, both of us eyeing his makeshift wooden target. Momoa is explaining the allure of throwing an ax, the sense of satisfaction and catharsis he gets from the thunk of a blade sinking into a wall, the testosterone boost he believes it delivers.

But I’m behind a beat—probably because I am 30 weeks pregnant, with a belly that makes me look like I’m smuggling a watermelon under my shirt. I’m in the final stretch for my firstborn and under doctor’s orders to avoid any new physical activities—“even yoga.” I briefly wonder if Dr. Caldwell would count chucking heavy axes as exercise, but Momoa seems unfazed. “Heyyy, mama,” he’d said by way of greeting when we met, pointing to my gut. “Look at that!”

Now he proceeds to hand me four sharpened tomahawks. He designed them himself, working with a local outfit to source the wood and forge the steel. The ax handle is as long as my arm; the blade is eight inches long. It’s heavy, and it feels awkward and unwieldy as I cock it behind my head and aim at a wooden target about 15 feet away.

“The trick,” Momoa says, “is to throw straight, release early, and don’t bend your wrist. People always bend their wrists, like they’re throwing a football spiral or a baseball.”

My eyes flick down to a bulbous stomach below, and then I let the tomahawk fly. The blade hits the wall flat. The second, third, and fourth tries drive into the dirt—I’m throwing down, releasing late.

“Should I, um, slow it down? Not throw so hard?” I ask.

“Fuck, no!” Momoa answers. “Throw it with all you’ve got.”

He’s patient through more failed attempts, quick with encouragement and tips. Step forward with confidence. Keep hips square to the wall. Throw harder. Yet despite the coaching, I can’t bury a blade into the wood.

Momoa offers to demonstrate. He backs up an additional 15 or 20 feet—“I’m going for the long shot,” he says. In quick succession—thunk, thunk, thunk, thunk—he sinks each ax into the center of a two-foot square on the wall and lets out a triumphant battle cry.

He walks back over to me, grinning. “Isn’t it so fucking fun?”

MOMOA’S HOUSE IS PERCHED on a hilltop on the outskirts of Los Angeles. Spread around the property is perhaps the most impressive array of toys I’ve ever seen, including a 25-foot climbing wall and a skateboard ramp.

I’m here with a Men’s Journal photo crew. The original plan was to meet the actor in a nearby canyon and photograph him bouldering there. But a day before the shoot, Momoa nixed that idea. He wanted something that felt more intimate, less produced. “It’s cool just to be at home,” he’d said. “It makes everyone feel more relaxed, and you don’t have to fake shit.” The crew has arrived early to set up for the afternoon cover shoot, and after unloading our gear and taking stock of the property, all we need is our subject.

He pulls up right on time, astride a black Harley-Davidson— engine revving, hard rock blasting, his long hair streaming behind a black helmet and handkerchief. He’s been on a beer run, he explains. On Momoa’s list of shoot requests, he’d put Guinness at the top, and we’d come with ample supply. Still, he says, “I wanted to make sure you got the right stuff.” He puts two more six-packs of Irish water, plus a sixer of Elysian Space Dust IPA, on ice in a pink Yeti cooler nearby.

He introduces himself to everyone, shakes firmly, grins wide enough that his face scrunches and his Polynesian eyes disappear. As the photo team sets up the first shot, he and I pull two rusty metal-wire chairs next to his climbing wall to talk. Momoa has invited a couple of friends over for the afternoon; he leans back in his chair, watching one of them testing a fresh route on the wall. “Feel free, Mariss,” he says, abbreviating my name as though the two of us are old buddies ourselves.

We’re here to talk about Aquaman, in which Momoa stars as the titular superhero—a trident-wielding deep-sea demigod with a conflicted past and a mission to, naturally, save our world. The actor seems typecast in the role, because Momoa comes off as a kind of superhero himself, a misfit who climbs, skates, rides, and surfs, who rips into raw steaks and washes them down with suds. Has this always been his vibe?

“Always,” Momoa says. “I’ve been climbing since I was 14. Skateboarding since I was 8. I love the outdoors, camping, I mean—obviously you saw the Airstreams. I used to live out of that one.” He gestures to a silver bullet a couple of hundred feet away. It was his home in his early 20s, when he was living the dirtbag climbing life in Valencia, about 40 miles north of Los Angeles, broke, with no acting career in sight, using a pager in place of a phone.

He nods to the climbing wall. “This is my love. It’s always kept me humble, grounded, outdoors, and pushing myself, scaring myself,” he says. “On the wall, it’s a flow—you’re problem-solving, creating something. It’s the perfect real-world mental and physical test.” He’s determined to teach that ethos to his kids—daughter Lola, age 11, and son Nakoa-Wolf, “Wolfie,” who’s 10. “That’s the coolest thing, when your kids love what you do,” he says. “They do hula and African dance with my wife, and they climb, skate, and surf with me. And they dig music.”

This last bit seems to light up Momoa. He describes how he taught his kids a song by the metal band Tool to surprise his Tool-loving assistant while on set for Aquaman in Australia. “We played ‘Sober.’ My son played guitar, my daughter played the drums, and I played bass. I could not believe that was my children’s first song,” he says, shaking his head.

Sudden, fierce obsessions are part of Momoa’s DNA. “If I see something I love,” he says, “I want to learn everything about it. There are just so many things I want to do in this life, from writing to music to designing to activism. I actually need more people to help me. I’m slowly building a little army.” He glances again at his buddy on the wall, a loyal member of his crew, who is making his way up a new route of holds.

Momoa pops open a Guinness and takes a long swallow. “You know, I met my wife over a pint of Guinness,” he says. “I knew it was love when she ordered it first.”

Right. His wife. That would be Lisa Bonet, former child star of The Cosby Show, widely (and, trust me, credibly) considered one of the most beautiful people alive, and whom I’d spotted walking along the yard’s periphery in a long, flowing skirt and cutoff T-shirt. The pair have been together since 2004, when a mutual friend introduced them at a jazz club. But Momoa’s attachment to Bonet goes back further, to when he first saw her on TV at the age of 8. He remembers thinking, “I’m going to stalk you for the rest of your life, and I’m going to get you,” he told James Corden on The Late Late Show last year.

I understand grand, public proclamations of love, I tell him, but what about their day-to-day relationship? Say, Tuesdays.

“I get in trouble just like any other dumb fucking male,” Momoa says. “We love each other, have an amazing family together, but a relationship is work.” He asks me how long I’ve been with my partner. Twelve years, I tell him. About the same for him, he says, and reflects on how much a person can change over such a long period. “That poor woman met me when I was 26,” Momoa says. “I was a maniac. I wanted to do all of these things, but I didn’t have an outlet, so I would just destroy. She’s stuck with me through too many me’s.”

DESPITE HIS EXOTIC LOOKS, Momoa spent his childhood in Norwalk, Iowa, a town of about 9,000 outside of Des Moines. He was born in Honolulu, son of a Hawaiian father and Midwestern mother. But his parents split when Momoa was young, and his mom took him back to her hometown. “I grew up where everyone was a wrestler or football player, and I was the skateboarder, an outcast,” Momoa says. He spent summers with his father on Oahu, but he was an outsider there, as well. “I wasn’t really accepted as a Hawaiian,” he says.

At 19, while working at a surf shop in Hawaii, he went to an open casting call for Baywatch: Hawaii. He beat out more than 1,300 actors for the part of pretty-boy lifeguard Jason Ioane. Momoa spent two seasons on the show and fell in love with acting. Unfortunately, he learned that it’s tough to be taken seriously when your main co-star is a rescue buoy. Unable to get an agent or book a job in the early aughts, he put his Baywatch cash toward other passions: climbing, traveling around the world, music, painting.

Momoa continued to act, scoring a supporting role on the TV show Stargate: Atlantis and the lead in the film remake of Conan the Barbarian. But his big break came in 2011, when he was cast as the bloodthirsty Dothraki chieftain Khal Drogo in Season 1 of HBO’s Game of Thrones. During the audition, he performed a version of the haka, a howling, foot-stamping, arm-waving Maori war dance; he later learned that had helped him land the part. (A Web search for “Jason Momoa GoT audition tape” would not be a waste of your time.)

Khal Drogo was a stoic, muscle-bound, shirtless warlord whose lines were grunted in the guttural, fictional Dothraki tongue. Sadly, the Khal was brutally stabbed in episode eight, fell into a catatonic state in episode nine, and perished in episode 10—when his beloved wife, Daenerys, mercifully smothered him with a pillow. Despite his newfound notoriety, Momoa again struggled to book jobs. “People didn’t think I spoke English,” he told Jimmy Fallon on The Tonight Show.

So Momoa took his career in his own hands. He made his directorial debut in 2014’s Road to Paloma, a low-budget thriller that he also co-wrote, produced, and starred in, alongside Bonet. The movie saw mild box-office success, but more importantly, it fueled Momoa, convincing him that he was good for more than rippling pecs and whooping battle cries. Soon after, he landed the lead role in Frontier, a Netflix drama about the outlaw fur trade in Canada in the 1700s; he has since co-directed some episodes.

And now there’s the role that could make Momoa a household name: Aquaman. The big-budget superhero film, a spin-off of last year’s A-lister-packed Justice League, is the first major motion picture the actor has carried. He stars as Arthur Curry, a half-human, half-Atlantean with the ability to command marine life. DC Comics originally drew the superhero as a lily-white blond in shellacked-on green tights and an orange blouse. Momoa is his antithesis—a brooder with wild, dark surfer hair and a bare, inked-up chest and limbs. “It’s probably the character I’ve played that’s most like me,” Momoa says. “Like him, I grew up a huge outsider. I was just with my mother, he was just with his father, and I know what that’s like, not having a parent around.”

His co-stars say that Momoa interpreted the role with nuance and care. “Jason loves to defy his physical persona; I actually think that’s his biggest strength,” says Patrick Wilson, who plays Arthur’s half-brother and archrival, King Orm. “The script pushes Arthur, brings out charm and humor while never sacrificing badassery.”

Momoa and Wilson engage in some epic fight scenes, and Momoa came away impressed with the help he got from his stuntmen on set. “I love those guys,” he says. “They bled for me.” He returned the favor by flying several of them to Canada to play small roles in Frontier. He also landed a Frontier role for Temuera Morrison, a New Zealand actor Momoa has admired since childhood, who played the part of Aquaman’s father at Momoa’s insistence.

“If I fall in love with you,” he says, “I put you in my pocket, and I take you everywhere.”

“I FEEL LIKE it’s time for a beer, anybody else feel that?” We’ve been shooting for 30 minutes. Momoa’s Warner Bros. rep brings the actor an IPA and a Guinness; he grabs the latter.

As the photo shoot progresses, Momoa has had his hands in everything. He instructs on when and where the light will be best, and after a series of shots, he huddles behind the camera to weigh in. He’s insisted on wearing his own clothes for some of the photos: Carhartts, thick leather belts with tarnished-metal buckles, washed-out shirts with Swiss-cheese holes. He’s DJing the music, which spans genres, from bluesy-acoustic country to New Orleans crooners to Tom Waits and the Rolling Stones.

During a break, we get to talking about some of his upcoming projects. First up is See, the Apple-produced series Momoa has just signed on to, playing a tribal leader in a dystopian future in which all humans are born blind. Though he’s again playing the heavy, Momoa says he’s eager to stretch out, to a comedy, maybe even a romance. He’s working on a script, a tragic Native American love story with a Shakespearian bent. It’ll be a low-budget venture, with the crew camping in his Airstreams. The irony of a blockbuster action star pinching pennies is not lost on him. “I’m not gonna blow up anything special. There’s no fucking special effects,” he says. “This is one of those films that’s just sitting by a fire telling stories—and it’s a great story.”

We’re interrupted by the photographer, who is beckoning us over to the bouldering wall for some action shots. Testing a few routes, Momoa yells and whoops—“Aha, you fucker!”—as he reaches for a higher grab. His style is all explosion and speed. He bounces in his heels before going for a big move, like he’s coiling before letting loose to ascend upward.

Standing beside me is one of Momoa’s friends, Dan Chancellor, co-founder of the climbing company So iLL; the two men are active in 1Climb, a nonprofit started by climber Kevin Jorgeson that aims to bring the sport to underprivileged kids. I ask Chancellor how he rates the actor’s skills on the wall. “I haven’t met a climber his size that’s as strong as he is. Ever,” Chancellor says. We watch as Momoa completes one last route, then polishes off another Guinness and chucks the can to the side.

Bonet walks down from the house to a huddle of people behind the camera, reviewing shots of Momoa posing in the couple’s greenhouse, where they grow squash, eggplants, carrots, basil, kale, arugula, collard greens. Bonet looks in closely at one shot, an image of Momoa hunched over a clump of carrots, a slight pudge sticking out at his waist. She laughs and clucks, “Uh-oh—look at that gut.” Momoa bellows back, “Baby, do not shame my stomach!” and slaps her backside. “I told you I’m gonna go Brando on your ass.”

The shoot is all but wrapped, the crew packing up. Momoa walks over. “Good luck, mama,” he says, giving me a tight hug goodbye. I look down at his arms and remember I have one last question. Momoa is famous for his tattoos: He has his children’s names, in their own handwriting, on his chest; the name of his production company, Pride of Gypsies, written out on his inner right forearm; a thick band of triangles, said to symbolize the teeth of a shark, his Hawaiian family’s guardian animal, runs up his left forearm. Like every object on this compound, the tattoos weren’t whims. They really mean something to him. But there’s an almost illegible scrawl on the outside of his right forearm, written in French, that I’ve been staring at all afternoon. What does it say?

“That’s a Charles Baudelaire quote,” Momoa replies. “It’s from my favorite poem. It means ‘Always be drunken’—with wine, with poetry, with virtue.”

I understand grand, public proclamations of love, I tell him, but what about their day-to-day relationship? Say, Tuesdays.

“I get in trouble just like any other dumb fucking male,” Momoa says. “We love each other, have an amazing family together, but a relationship is work.” He asks me how long I’ve been with my partner. Twelve years, I tell him. About the same for him, he says, and reflects on how much a person can change over such a long period. “That poor woman met me when I was 26,” Momoa says. “I was a maniac. I wanted to do all of these things, but I didn’t have an outlet, so I would just destroy. She’s stuck with me through too many me’s.”