300: Movie Vs. Reality

The ”300” movie made quite an impression when it was released in 2006. Based on the homonymous comic book by Frank Miller, the movie earned a huge fan base around the world.

Like the comic book, the “300” takes inspirations from the real Battle of Thermopylae and the events that took place in the year of 480 BC in ancient Greece. An epic movie for an epic historical event.

However, how close was the movie to the actual events and characters? And going beyond the 300 movie, what was the context of the Battle of Thermopylae and who were really the Spartans and Leonidas?

Artwork for the Battle of Thermopylae – Credit: Cleber.knfire [CC BY-SA]

300: The Movie

The film ‘300’ focuses on one battle during the long Greco-Persian Wars, the armed conflicts between the Persian Empire and the Greek city-states of the time. In 480 BC, the King of Persia, Xerxes, demands the subjugation of Sparta to his rule.

The Spartans, however, being proud and honorable warriors, could not accept such an offer. King Leonidas, despite the objections of the Senate and the ominous oracles, decides to confront Xerxes’ numerically superior forces in the strait of Thermopylae. He guides a force of 300 heroic Spartan warriors towards the battlefield and a few hundred more Thespians join their forces.

Zack Snyder’s film was not shot in order to teach history lessons. The “300” movie is based on the eponymous comic book by Frank Miller (creator of “Sin City”), which presents only a free version of the battle, enriched with several fantastic elements. Therefore, historical inaccuracies are unavoidable and excusable since the film is not based on real history but on a fantasy graphic novel.

Nevertheless, since the movie was the reason that many people around the world discovered this part of history and the glorious battle and sacrifice of the 300, let’s see what the movie got right and wrong, and go beyond it by discovering the real events and who the Spartans really were.

Remains of ancient Sparta, ruins of theater. The modern city and fragment of the Taygetus mountain in the background

Credit: WitR / Shutterstock

The “300” Movie vs. the Historical Events

Frank Miller, author of the graphic novel “300” on which the homonymous film was based, said that he traveled to Greece and researched history as much as he could. He walked the battlefields and took into account the historical elements in the writing of the work.

However, he clarified that his work was not a realistic representation of the historic battle of Thermopylae, but a free version of the battle that contains several fantastic elements. So, let’s see what the actual differences were between the “300” movie and the historic battle of Thermopylae.

The Statue of King Leonidas in Thermopylae

Credit: Anastasios71 / Shutterstock

The Status Quo in Greece

Let’s start with the geopolitical reality of the time. The film hints that the Spartans were the only Greek resistance against the Persians – the only big Greek force that cared to stop the Persian invasion. This, of course, is not true. There were coordinative efforts between many Greek city-states (most of those that were still free and have not already fallen under the Persian rule).

For the first time in Greek history, there was an alliance with the foremost purpose to unite all anti-Persian forces in the whole Greek world. The strategy for countering the Persian invasion was discussed in a war council that took place in Isthmus of Ancient Corinth. During the war council, many Greek city-states took part, among which was Sparta, Thebes and Thessaly. The Athenian general and politician Themistocles was also in the council and he was the key figure in uniting the Greek powers and devising the battle plans.![Credit: Bibi Saint-Pol <a target='_blank' href='http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/'>[CC BY-SA]</a> Map during the Greco-Persian Wars (only a small part of the Persian Empire is shown)](https://greektraveltellers.com/images/Blog/300/Greco_Persian_Wars_map_300.jpg)

Map during the Greco-Persian Wars (only a small part of the Persian Empire is shown)

Credit: Bibi Saint-Pol [CC BY-SA]

The War Strategy

Knowing the overwhelming numbers of the enemy, the Greek war council decided that it was important to have two decisive battles, one by land and one by sea. Spartans would be leading the infantry and the Athenians the navy. The hope of the Greeks was the new Athenian fleet. No one dared to think that it would be possible to make a decisive blow against the Persian land troops. The plan originally was to stop the invasion at the valley of Tempi, south of Olympus.

However, they soon abandoned this plan because they could be circled easily from the west and they were not sure of the intentions of the Thessalian people, who indeed allied with the Persians soon after. So, they changed their battle plans and decided to make their stand at Thermopylae. The landscape of Thermopylae could help the Greeks gain some advantages that could neutralize the superior numbers of the Persian army: the straits hindered the development of the enemy’s ground forces, while the small strait of Artemisium ruled out a possible encirclement of the collaborating Greek fleet. If they managed to keep the advance of the Persian army on Thermopylae for a short time, maybe the fleet would have the opportunity, if the conditions were favorable, to get a decisive victory.![Credit: BMartens <a target='_blank' href='https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/'>[CC BY-SA]</a> The battle of Thermopylae](https://greektraveltellers.com/images/Blog/300/Battle-of-Thermopylae.jpg)

The battle of Thermopylae Credit: BMartens [CC BY-SA]

The “300” movie shows Leonidas defying the corrupted Spartan political leadership and charging with his elite guard to Thermopylae, to defeat the Persians by themselves.

However, this is not how the events really took place. When the Spartans were informed of the advancement of the Persian army and the need to march their forces to Thermopylae, there were confronted with a problem.

At that time, they were celebrating their religious festival called “Carnea”, in honor of Apollo Carneios. The festival was held once every year and lasted for 8 days. During the festival, no armed conflict was allowed, in a similar fashion to the Ancient Olympic Games. The Spartans decided to send one of their two kings, Leonidas, with his personal guard and delay the Persians until the whole Spartan army arrives. The rest of the army would march right after the religious truce was over, hoping that they would arrive in time.![Credit: Joaquin Ossorio Castillo / Shutterstock Molon labe, meaning “come and take [them]”, the famous reply of Leonidas to Xerxes](https://greektraveltellers.com/images/Blog/300/Molon-lave_Joaquin-Ossorio-Castillo_Shutterstock.jpg)

Molon labe, meaning “come and take [them]”, the famous reply of Leonidas to Xerxes

Credit: Joaquin Ossorio Castillo / Shutterstock

The Heroes

When it comes to the battle at Thermopylae, the 300 movie is quite far from reality. Leonidas leaves Sparta with only 300 men and on their way to Thermopylae a small force of Arcadians led by Daxos join them. However, there were more men present in the battle of Thermopylae.

With the 300 men of Leonidas, there were about 3800 Peloponnesians (Lacedemonians, Arcadians, Corinthians, Tegeans, Mantineans, Philians and Myceneans). Besides the Peloponnesians, there we also 700 Thespians, 1000 Phocians and 400 Thebans. The total army marching to Thermopylae numbered about 6200 men. Another 900 men should be added to this number to account for 3 helots (slaves of Sparta) serving each Spartan warrior.

Not all of them fought in the battle. Leonidas assigned the 1000 Phocians with guarding the mountain passage that could encircle their position if found by the Persians. When Ephialtes betrayed the Greeks and showed the passage to Xerxes, a runner informed Leonidas that they were about to be encircled. In the movie, it is Daxos of the Arcadians that informs Leonidas and then leaves the battlefield with his troops. In reality, upon discovering that his army had been encircled, Leonidas told his allies that they could leave if they wanted to. Part of the army took him up on his offer and fled.

However, around 2000 men stayed behind to fight and die. The 700 Thespians, led by their general Demophilus, refused to leave and committed themselves to the fight. The 400 Thebans also stayed to sacrifice themselves. The helots who had accompanied the 300 Spartans were probably also present.

Knowing that the end was near, the remaining Greek forces marched into the open field and met the Persians head-on. Considering that the 700 Thespians and the 400 Thebans were not professional soldiers like the 300 Spartans and were not trained from an early age to fight and die in honor, their decision to stay and fight till death may seem by some even more heroic than the 300’s.

The monument of the 700 Thespians in Thermopylae

Credit: Greek TravelTellers

The Battle

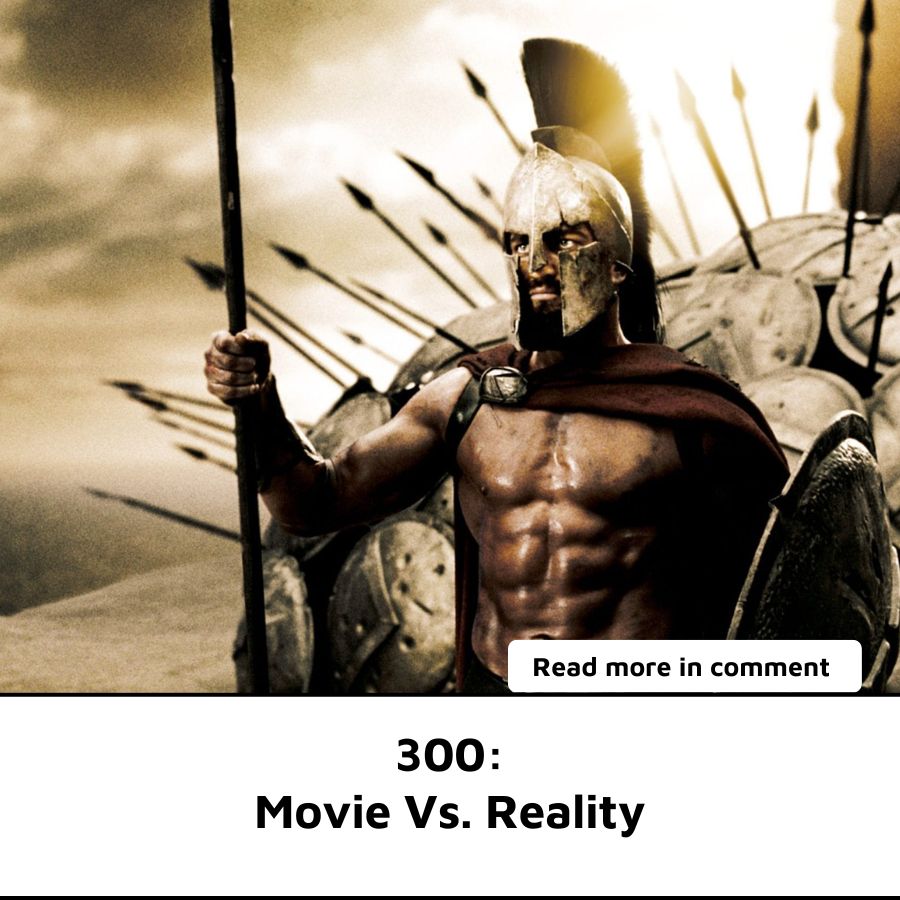

As for the battle itself, there are many differences from the real battle, that were made for cinematic purposes. For example, the 300 film shows the Spartans half-naked during the battle without any armor to protect their upper body, which was not the case with the real Spartan warrior.

Spartans relied a lot on their body armor. They wore grieves over their legs, a breastplate and a helmet. By this period, the solid bronze armor plates have been replaced with pieces made from layers of linen stuck together, stiffened by immersion in vinegar and salt, and reinforced with layers of bronze. They also carried a large round shield, very similar to the movie’s, a long lance and a short iron sword.

On the right: a Spartan warrior in the 300 movie. On the left: how Spartan warriors looked like in reality.

Spartan Warriors

When it comes to the battle formation, the movie made significant changes again for cinematic purposes. The true strength of the Spartan army came from their battle formation, the phalanx! The strength of the phalanx relied on all men working together as one unit.

Each warrior protected the one next to him with their shield, the most important equipment of a Spartan warrior. In the movie, the Spartan warriors break their formation on many occasions and run loose towards their enemies, fighting one to one. This would never happen in the real battle of Thermopylae, otherwise the ‘Hot Gates’, as it translates in English, would fall in an instant.![Credit: John Steeple Davis [Public domain] The Spartan Phalanx against the Persian army](https://greektraveltellers.com/images/Blog/300/300-movie-Spartan-phalanx.jpg)

The Spartan Phalanx against the Persian army

Credit: John Steeple Davis [Public domain]

The Characters

It is important to mention that King Leonidas was not the only King of Sparta. Sparta had two kings at the same time. When one was at war away from Sparta, the other was at home, looking at the political affairs and protecting Sparta from anarchy or uprising of the helots. In the movie of 300, King Leonidas is portrayed by Gerard Butler as a young man, probably around his 30s. The real King Leonidas was aged around 60(!) when he fell in Thermopylae.

King Xerxes had a beard and was, of course, much shorter than his character in the film. He never went to the front line of the Battle of Thermopylae and never had a face-to-face conversation with Leonidas.

Statue of King Leonidas

Credit: Nick Kom / Shutterstock

In the movie, Dilios, the Spartan warrior who lived to tell the story, is injured in the eye and is instructed by Leonidas to return to Sparta and tell everything that happened in Thermopylae. At the end of the movie, Dilios is shown as leading the united Greek army against the Persians in Plataea.

The reality, however, is much different. There were two Spartan warriors who were stricken with a disease of the eye, according to Herodotus. Their names were Aristodemus and Eurytus. Leonidas ordered them to return to Sparta before the battle was over. However, Eurytus ordered his helots to take him back to the battle, though blind, and met his end charging into the fray. Aristodemus returned to Sparta and his fellow citizens saw him as a coward. He was subjected to humiliation and disgrace and was known as Aristodemus the coward. The fact that Eurytus had charged back in battle and met his fate was probably the reason for this treatment.

Aristodemus’ story doesn’t end there though. He endured all this humiliation and joined the army at the Battle of Plataea the following year. According to Herodotus, the Spartan warrior fought with such fury that the Spartans regarded him as having redeemed himself. However, they did not award him any special honors for this valor because he had fought with suicidal recklessness.

The Spartans valued more those who fought bravely while still wishing to live. Aristodemus charged, berserker-like, out of the phalanx and fought, in the opinion of the historian, with the most bravery of all the Spartans before falling in battle.

Scene from the memorial at Thermopylae

Credit: Joaquin Ossorio Castillo / Shutterstock

The Discarding of Unfit Offspring

The movie starts with the birth of a child in Sparta and its inspection. “If he’d been small or puny or sickly or misshapen… he would have been discarded.” Plutarch is the only source we have on the matter. According to the Greek historian (who lived half a millennium after the Battle of Thermopylae):

“If after examination the baby proved well-built and sturdy they [the state] instructed the father to bring it up, and assigned it one of the 9,000 lots of land. But if it was puny and deformed, they dispatched it to what was called ‘the place of rejection’, a precipitous spot by Mount Taygetus, considering it better both for itself and the state that the child should die if right from its birth it was poorly endowed for health or strength.”![[Public domain] “The Selection of Children in Sparta”, painting by Jean-Pierre Saint-Ours in 1785](https://greektraveltellers.com/images/Blog/300/Killing-of-babies-in-Sparta---myth-or-reality.jpg)

“The Selection of Children in Sparta”, painting by Jean-Pierre Saint-Ours in 1785

[Public domain]

However, recent studies have come to dispute the above statement. Athens Faculty of Medicine Anthropologist Theodoros Pitsios says after more than five years of analysis of human remains culled from the pit, researchers found only the remains of adolescents and adults between the ages of 18 and 35. “There were still bones in the area, but none from newborns, according to the samples we took from the bottom of the pit” of the foothills of Mount Taygete near present-day Sparta.

According to Mr. Pitsios, the bones studied to date came from the fifth and sixth centuries BC and come from 46 men, confirming the assertion from ancient sources that the Spartans threw prisoners, traitors or criminals, into the pit. He adds that the throwing of unfit babies “is probably a myth, the ancient sources of this so-called practice were rare, late and imprecise.” Meant to attest to the militaristic character of the ancient Spartan people, moralistic historian Plutarch in particular spread the legend during first century AD, more than 500 years after the Battle of Thermopylae.